He may be dog number three and has only been here for a little over a year, but Chip has already started teaching us so much – and reinforcing previous lessons.

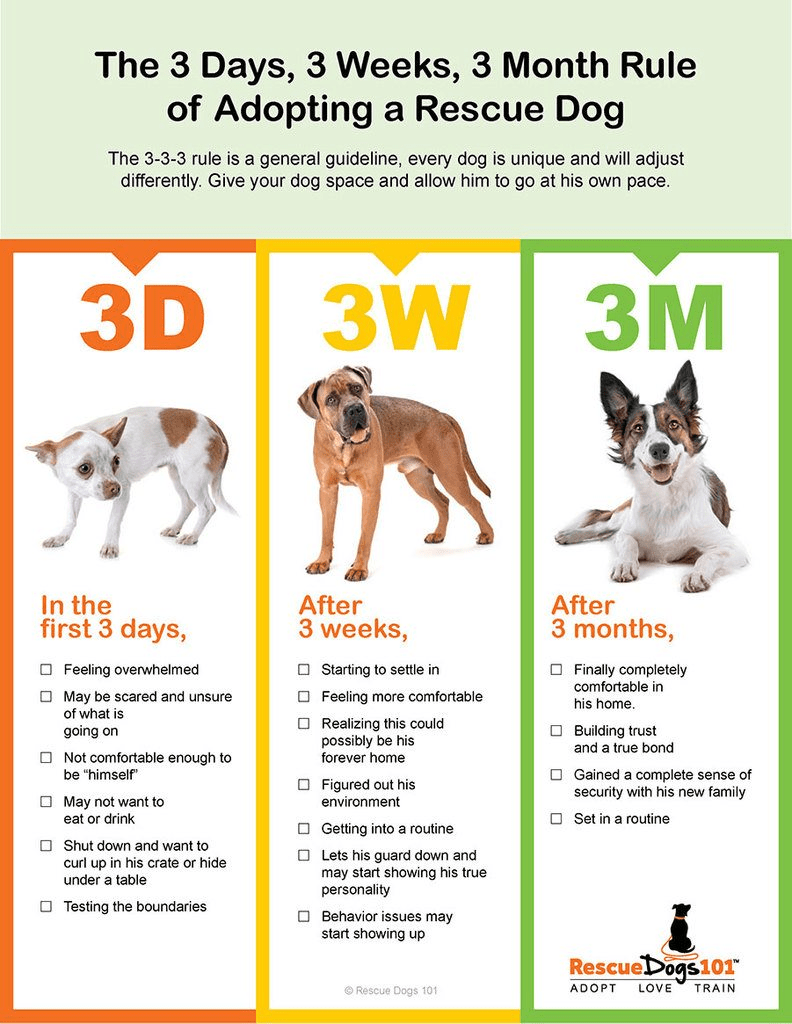

3-3-3 Rescue Rule

Long before bringing Chip home, I learned about the 3-3-3 rescue rule. In a nutshell, it says that rescue dogs need three days to decompress, three weeks to learn your routine, and three months to feel at home.

It’s a general rule and not something that applies consistently across all rescues since every dog is different! When I first heard of this “rule,” it made perfect sense, though it didn’t seem to apply quite exactly with Cookie or Ziggy. They adjusted more quickly.

Meanwhile, this has fit Chip very well, but he’s probably taken a little longer with each phase. So far, Chip is our most challenging dog and can cause more frustration. BUT, it is SO rewarding to see how far he has come. Part of it is natural growing up, another part is continuing to adapt to a safe, loving, and stable environment, and yet another part is us figuring out and meeting his needs (i.e. sufficient enrichment and exercise).

This approximate timeline is important to consider when deciding to rescue. Be prepared to invest the appropriate amount of time before your new pack is running smoothly. Each dog will be different based on their history (which the degree of known detail will vary based on the circumstances they were found/surrendered) and their individual personality.

Bottom line: Be patient. Work with your pup and seek out professional trainers to help your pup adjust.

Barking is trainable

Cookie and Ziggy are not avid barkers. Sure, they’d bark if a delivery was being made or “suspicious” people walked past our house. But that was mostly it. Any other time they needed to communicate they would use their eyes or body language.

Not Chip. He is a “chatty Cathy.” While I believe that’s partially due to him having husky in him, it’s also been reinforced one way or another. Barking is a form of communication, and while we may not agree with the importance of why they’re barking, dogs are trying to communicate something when they bark.

For example, when I would shower and get ready for work, I would crate Chip in our bedroom just outside the master bath. At first, he would bark non-stop. Fortunately, I was able to be in his line of sight if I left the door open. So, when he was quiet, I would reward it – with LOTS of verbal praise and treats, when I could.

He quickly learned that I was nearby and that he didn’t need to narrate the entire time I was in the shower.

Other scenarios are harder to train (though professional trainers are more likely to offer up better tools than me), but with time they’re doable. In the beginning, for many reasons, we would walk Cookie and Chip separately. We couldn’t always ensure that one of us was home with Chip while Cookie would get walked. So he was crated, and for Cookie’s 20-minute walks, Chip would bark almost non-stop.

Over time, he grew more confident that he wasn’t being abandoned and that we always came back. We also slowly started testing the waters leaving him uncrated during her walks. Thankfully, those experiments were successful, and the combination of time and being uncrated worked for Chip.

Bottom line: The key with barking is to make sure you reward the silence, not the barking – particularly in scenarios where the barking isn’t appropriate. Barking is a natural dog behavior and shouldn’t be eliminated, simply managed. Find professional trainers that can help you modify the behavior.

Reactivity isn’t a bad word

Before Chip, “reactivity” had a bad connotation for me. I took it to mean an aggressive, unapproachable, unsocial dog. But it’s not.

Reactivity is simply a dog responding to stimuli in the environment. It could be for a multitude of reasons including overexcitement and fear.

I’m still learning how to best support Chip and set him up for success. Sometimes his reactivity is clearly fear, and other times excitement. Those are his main drivers, but there are other times when it’s hard to tell.

We’ve taken a training class specific for reactive dogs, and I continue to learn by following experts such as Dynamite Dog Training (one of several of Chip’s teachers), r+dogs, and Dog Training Academy Florida.

Bottom line: Be open to the “reactive” dog label. Whether your dog is reactive or not, I encourage learning more about reactive dogs because it can help you support pawrents of reactive dogs when you encounter them.

Life lesson: Stay tuned

One year in is too early to pick Chip’s life lesson, so you’ll have to stay tuned as he grows up to see what else he teaches us!